English Landscape Garden Style

English Landscape Garden style was a design movement that was popular in 18th Century England. The English Landscape Garden is also simply known as the English Garden. This style was a sharp contrast from the French Garden or Baroque styles that were previously the dominant look of gardens in Europe.

English Landscape Gardens favored a more naturalistic vibe than the symmetrical and geometric formality of French Gardens and the Renaissance styles. This style was only possible to achieve on large-scale land holdings found on the grounds of large country homes, castles, and palaces in the English countryside. These were originally for the exclusive pleasure of aristocrats and guests, although many now exist as parks for the public to enjoy. As such, this is a style that cannot be emulated in residential gardens and is a style that is limited to use in large parks.

This design movement became trendy during the reign of King George III. This is also called the Georgian era of English history. During the Georgian era, England lost control of their colonies in North America. Despite this loss of territory, England remained a proud imperial nation and English landscape gardens used many trees and shrubs that were discovered by colonists around the world.

Defining Features

The defining features of English Landscape Gardens were typically centered around a lake, from which vistas would be carefully crafted from rolling grass hillsides surrounded by groves of trees. The lake would be crafted in a serpentine shape so that it would curve away out of view to entice you to explore further.

The Folly

At key focal points, follies would be placed to create an idyllic landscape that resembled romantic landscape paintings of that era. A folly is a term derived from the French "folie" (meaning foolishness) and is also known as an "eyecatcher". Follies in English Landscape design were non-functional buildings and often based on antique structures such as Roman temples or medieval ruins. These follies would often be built on a smaller scale than the real versions of these structures to create an illusion of distance and make the landscape feel much bigger.

Vista Points

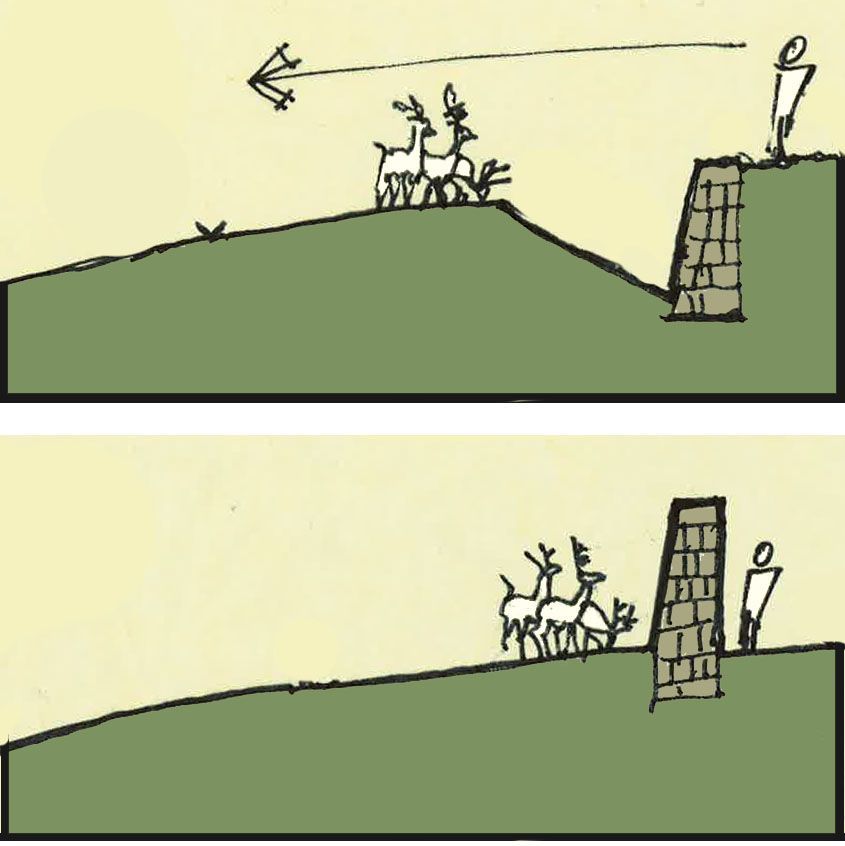

Views in English Landscape gardens would be designed so that a distinct foreground, middle ground, and background could be perceived by the viewer. Well-designed landscapes in this style would be created in a way that only reveals the follies at a specific vista point, creating an element of surprise as visitors walk around the central lake.

Landscape art of this era would typically depict pastoral landscapes with ancient temples or other picturesque follies in the background. Scenes like this were often mimicked in the English Landscape Gardens.

"Ha-Ha"

Another distinctive element of this style is the "Ha-Ha". A ha-ha is a wall sunken into the ground on a property boundary that has a trench on the other side to create a barrier without impeding views. As this structure is not apparent to you until you are right on top of the wall, it surprises visitors to the landscape. The name came from the resulting exclamation of surprise: "Ha-ha!". A ha-ha allows uninterrupted views further out into the landscape where livestock could graze without wandering into the manicured lawns of the foreground. The Ha-ha is a design element that can be adopted in residential landscapes if you have a large plot of land as an alternative to a large wall for keeping out wildlife. Of course, when used on a residential scale, the drop from the ha-ha could cause injury and a barrier if often required in local building codes. A cable railing would provide a safety barrier that will not obstruct the view.

Prominent English Landscape Style Designers

The original proponents of the style were the Landscape Designers William Kent and Charles Bridgeman. Later in the 18th Century, Lancelot 'Capability' Brown worked for Kent, and became the most celebrated of all Designers of the English Landscape Garden style, having worked on 170+ gardens in grand estates. Humphry Repton was the last great designer of the English Landscape style and is considered the spiritual successor to Brown.

Examples of English Landscape Gardens

Due to the large scale of a typical Landscape Garden, many exist today as public parks. Sadly, many estates were on parcels of land that have since been subdivided into smaller lots as the population increased in England, and the aristocracy lost their hold on the vast areas of land they held. As a result, many of the Landscape Gardens have been lost over time. Here are some notable examples that have survived and can be visited in the 21st century:

Claremont

The grounds of Claremont House in Esher, Surrey form the Claremont Landscape Garden, which is one of the oldest surviving English Landscape Gardens. This Landscape Garden was created for the Duke of Newcastle, Thomas Pelham-Holles. Claremont's gardens were created by Charles Bridgeman in 1720, who designed a more formal garden that was later revised to a landscape garden by William Kent in the 1730s.

Stowe

The gardens at Stowe in Buckinghamshire are considered to be the most significant example of the English Landscape Garden style. Originally landscaped as a small Parterred garden in the 17th century, Stowe was worked on by Bridgeman, Kent, and Brown in successive phases throughout the 18th century. This is the only garden where all 3 of the great English Landscape Designers worked on the same landscape. The design of Stowe Gardens became a great influence on many other parks and private estates over the next 200 years after its inception, influencing the design of Central Park in New York and London's Hyde Park.

Stourhead

Sitting at the source of the River Stour in Wiltshire, Stourhead garden is one of the most famous examples of the English Landscape Garden style. Stourhead was designed by Henry Hoare II and installed between 1741 and 1780. The views in the garden are inspired by Landscape paintings by Claude Lorrain, Poussin, and Gaspard Dughet. As with many other Landscape Gardens, Stourhead is anchored by a central lake. Follies visible from a path around the lake are designed to evoke the Greek myth of Aeneas's descent into the underworld.

The Englischer Garten

The English Landscape style was admired in other countries and many parks in Europe were designed in a similar manner. Germany's Englischer Garten (German for "English Garden") is one of the biggest urban parks in the world. This English Landscape garden park sprawls from the suburbs to the centre of Munich with numerous follies and sweeping vistas for the public to enjoy. The Englischer Garten was created by Sir Benjamin Thompson in 1789 for Prince Charles Theodore of Bavaria.

Revolutionary Design

There is an interesting urban legend as to why Prince Theodore commissioned the park for public use. Theodore was not well-loved by Bavarians and was in fear of a similar revolution as seen recently in France, North America, and many other places in the late 18th century. It is said that he wondered why there was no revolution in England and assumed the populace was kept happy with the many great parks and green spaces of English cities. As such he decided to build a park in the most fashionable style of the time, for the people's pleasure.

Eisbachwelle

Another interesting aspect of the Englischer Garten is that a small part of it has become a mecca for surfers in this city, which is located almost 300km from the nearest ocean. The artificial Eisbach River was created as part of the original design and rocks situated near a bridge on Prinzregentenstrasse created a standing wave that is now a popular attraction in the centre of Munich. This is known locally as the Eisbachwelle.

This surf break was discovered by a G.I., stationed in Munich, surfing the wake of the Second World War. It is a fair gnarly break that has a stationary wave set. Surfers and Kayakers line up on the banks of the Eisbach to wait their turn as each rider can ride the wave for as long as they can.

The city of Munich allows the Eisbachwelle to continue to exist, despite it's anarchic nature. A dank smell hovers over this spot, just yards away from the Swiss consulate and the National Museum. This is truly a park for the people.

Painshill

Painshill Park in Cobham, Surrey is a restoration of the English Landscape designed grounds of Painshill House. Painshill was built between 1738 and 1773 by Charles Hamilton. While not as celebrated as the previous examples, I had the pleasure of visiting Painshill on a recent trip to the UK and I think it would be useful here to walk you around the park as I did. This should demonstrate how English Landscape Parks present themselves to visitors, using the defining features of this design movement.

Painshill Tour

After entering Painshill through their cafe/gift shop area, you are immediately presented with a sweeping vista of a grassy field, bordered by groves of trees that hide the rest of the park from view. The campestral scenery is a sharp contrast to the suburbia surrounding the park's entrance. It immediately feels like you have been transported into an idyllic landscape from a classic painting.

Following the path behind this view, you pass through the trees and find yourself on the path around the lake. From here, the first folly comes to view, beckoning you to walk further to get a closer view.

The folly seen in the distance is the abbey ruins. This folly is one of the few that are original to Painshill, with others being restored or recreated after the garden itself fell into ruin before being made into a public park. This park feature is an example of a Gothic folly. Gothic follies were nostalgic memories of medieval times for the Georgians. It was designed as a "Romantic Ruin" and on the day that I visited a wedding was taking place there.

Continuing on the outer path of the lake, you see more follies at the other end. From here, you can see Woolett Bridge and a glimpse of the grotto, which is one of the main attractions at the park. Also visible in the centre of the background is the Great Cedar, a 300+ year-old tree that is the largest multi-stemmed Cedar in Europe. Woolett Bridge was designed to lead your eye and beckon you toward the island where the grotto is situated.

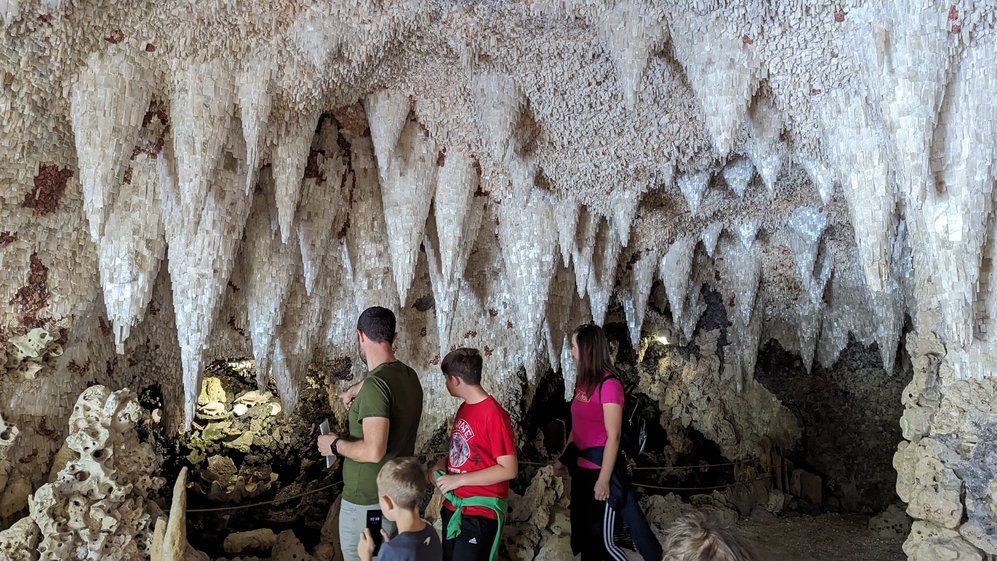

After crossing the bridge, from which several follies are visible in the distance, a path leads you to the crystal grotto, a stunning fantasy scene with seashell floors and a cavernous structure decorated with thousands of crystals that are illuminated by the sun reflecting off the lake.

Upon exiting the grotto you see the views from the other side of the lake, with a gothic temple placed high in the landscape. From here, you can continue in several directions - heading towards the Gothic temple leads you to the Chinese bridge (currently under repair), a vineyard, and a closer view of the ruined abbey.

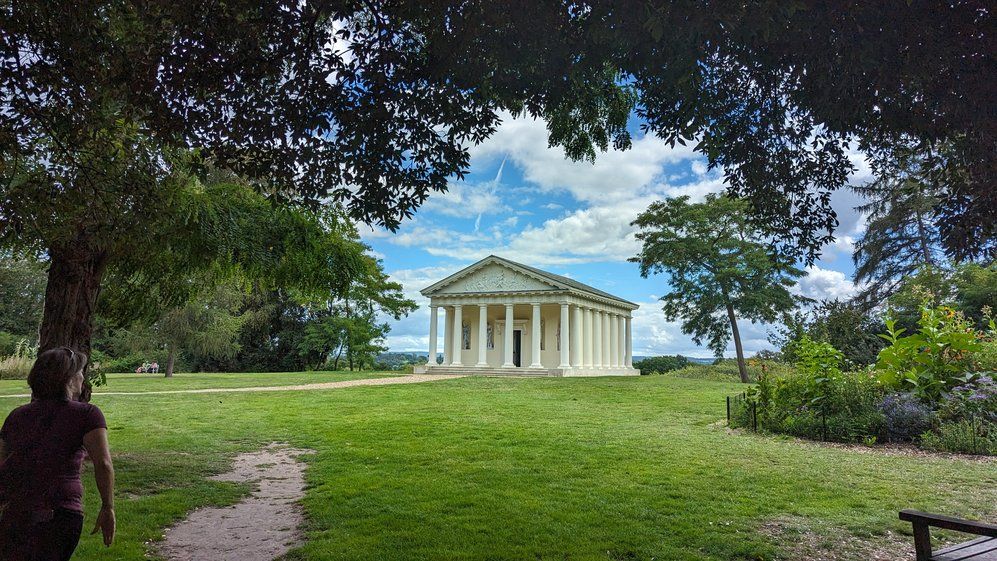

The paths around the lake are paved and accessible to all. While there is much to see here, the park has a large area to the rear of the grounds where it is much more wooded and the follies in this area are a continuous series of surprises. In the distance from where the path forks in either direction, a Roman temple peeks out of the trees, enticing you to explore this area.

Before moving to this area, you pass by one of several picture frames that have been mounted to show the perfect angles for viewing the landscape. These frames help you imagine exactly how Charles Hamilton designed the park to look like several landscape paintings that he would show off to guests as he gave walking tours of the grounds. I thought this was a very fun way to explore the scenery and situate yourself for the best camera angles of each vista point.

Walking down the path to the rear of the park, you pass by a waterwheel that was created to power pumps that pull water from the River Mole into the artificial lake. Venturing further, you turn a corner and suddenly see the Gothic tower looming large in the background of this wooded area.

Before you reach the tower, a small diversion can be made to one of the most interesting and quirky features in the park. Hidden amongst a densely wooded area at the back of the park is a small rustic hut known as the hermitage.

Hamilton built the hermitage to house a resident hermit for the amusement of his guests. In exchange for £700 (around £150,000 in today's money), the hired hermit would live in isolation, stay silent, and pray for the family, while living a simple life in the woods. As crazy as this sounds, ornamental hermits were a common sight in 18th-century English Landscape Gardens. Legend has it that Painshill's hermit only managed a few months of silent contemplation, and was fired after being discovered drowning his sorrows at a local pub.

After the Hermitage, the path leads you up through dense woods to the Gothic Tower. You can climb the circular stairs to reach the roof, where you can view the greater landscape. Be careful on the way down as the circular stairs can make you dizzy!

The path then leads you past the Temple of Bacchus, and a Turkish Tent, while offering views looking down onto the lake.

The viewpoint by the Turkish Tent has a picture frame, showcasing this scene of the lake with the Five Arch Bridge in the foreground, and the Grotto and Gothic Temple visible in the background. Compare the bridge in the image below with the bridge in the image above from Stourhead. Picturesque arched bridges like this were a common sight in the grand English Landscape Gardens.

The path leads you back down the hill, joining back to the lake path. From here, one can see views of the inner lake path follies. If you have time, you can explore more of the park in that area for a closer look at the abbey and vineyard as well as planting areas and statuary. Allow 1-2 hours for the short walk around the lake, and 3-4 hours to explore the entire park.